Tale fenomeno portò con sè dei gravi effetti collaterali: inquinamento, invivibilità delle zone industriali, durissime condizioni di lavoro...

Dickens si interrogò sui mutamenti della società e, con una nitidezza di vista che manca a molti sociologi odierni, li descrisse in maniera straordinaria.

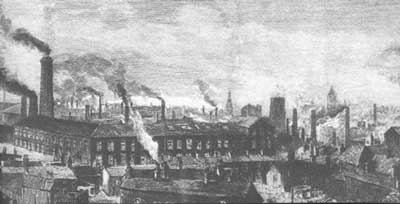

Una delle sue metafore più calzanti è quella di Coketown, "Citta del Carbone", il cui nome rimanda alla materia base dell'industria dell'800. Era una città mostruosa, riconoscibile da lontano per i fumi neri e la cappa di smog che la sovrastavano. Gli edifici erano brutti, di mattoni anneriti dall'inquinamento. Un tale luogo aveva effetti drammatici sulle persone che ivi vivevano, e cemento e rassegnazione si mischiavano per generare la loro <forma mentis>.

Particolarmente importante è il cap. V dell' opera "Hard Times".

|

"It was a town of red brick, or of brick that would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it; but as matters stood, it was a town of unnatural red and black like the painted face of a savage. It was a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled. It had a black canal in it, and a river that ran purple with ill-smelling dye, and vast piles of building full of windows where there was a rattling and a trembling all day long, and where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down, like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness. It contained several large streets all very like one another, and many small streets still more like one another, inhabited by people equally like one another, who all went in and out at the same hours, with the same sound upon the same pavements, to do the same work, and to whom every day was the same as yesterday and to-morrow, and every year the counterpart of the last and the next. These attributes of Coketown were in the main inseparable from the work by which it was sustained; against them were to be set off, comforts of life which found their way all over the world, and elegancies of life which made, we will not ask how much of the fine lady, who could scarcely bear to hear the place mentioned. The rest of its features were voluntary, and they were these. You saw nothing in Coketown but what was severely workful. If the members of a religious persuasion built a chapel there—as the members of eighteen religious persuasions had done—they made it a pious warehouse of red brick, with sometimes (but this is only in highly ornamental examples) a bell in a birdcage on the top of it. The solitary exception was the New Church; a stuccoed edifice with a square steeple over the door, terminating in four short pinnacles like florid wooden legs. All the public inscriptions in the town were painted alike, in severe characters of black and white. The jail might have been the infirmary, the infirmary might have been the jail, the town-hall might have been either, or both, or anything else, for anything that appeared to the contrary in the graces of their construction. Fact, fact, fact, everywhere in the material aspect of the town; fact, fact, fact, everywhere in the immaterial. The M’Choakumchild school was all fact, and the school of design was all fact, and the relations between master and man were all fact, and everything was fact between the lying-in hospital and the cemetery, and what you couldn’t state in figures, or show to be purchaseable in the cheapest market and saleable in the dearest, was not, and never should be, world without end, Amen. A town so sacred to fact, and so triumphant in its assertion, of course got on well? Why no, not quite well. No? Dear me! No. Coketown did not come out of its own furnaces, in all respects like gold that had stood the fire. First, the perplexing mystery of the place was, Who belonged to the eighteen denominations? Because, whoever did, the labouring people did not. It was very strange to walk through the streets on a Sunday morning, and note how few of _them_ the barbarous jangling of bells that was driving the sick and nervous mad, called away from their own quarter, from their own close rooms, from the corners of their own streets, where they lounged listlessly, gazing at all the church and chapel going, as at a thing with which they had no manner of concern. Nor was it merely the stranger who noticed this, because there was a native organization in Coketown itself, whose members were to be heard of in the House of Commons every session, indignantly petitioning for acts of parliament that should make these people religious by main force."

|

"Era una città di mattoni rossi o, meglio, di mattoni che sarebbero stati rossi, se fumo e cenere lo avessero consentito. Così come stavano le cose, era una città di un rosso e di un nero innaturale come la faccia dipinta di un selvaggio; una città piena di macchinari e di alte ciminiere dalle quali uscivano, snodandosi ininterrottamente, senza mai svoltolarsi del tutto, interminabili serpenti di fumo. C’era un canale nero e c’era un fiume violaceo per le tinture maleodoranti che vi si riversavano; c’erano vasti agglomerati di edifici pieni di finestre che tintinnavano e tremavano tutto il giorno; a Coketown gli stantuffi delle macchine a vapore si alzavano e si abbassavano con moto regolare e incessante come la testa di un elefante in preda a una follia malinconica. C’erano tante strade larghe, tutte uguali fra loro, e tante strade strette ancora più uguali fra loro; ci abitavano persone altrettanto uguali fra loro, che entravano e uscivano tutte alla stessa ora, facendo lo stesso scalpiccio sul selciato, per svolgere lo stesso lavoro; persone per le quali l’oggi era uguale all’ieri e al domani, e ogni anno era la replica di quello passato e di quello a venire.

Questi attributi di Coketown erano in gran parte inseparabili dall’industria che dava da vivere alla città; su questo sfondo, in contrasto, c’erano gli agi del vivere che si diffondevano in tutto il mondo; c’erano la raffinatezza e la grazia del vivere che contribuivano – non indaghiamo in quale misura – a creare quella gentildonna elegante che storceva il nasino al solo sentir nominare il luogo or ora descritto. Non c’era nulla a Coketown che non stesse a indicare una industriosità indefessa. Se i seguaci di una setta religiosa decidevano di erigere una chiesa – cosa che avevano fatto i seguaci di diciotto sette – ne saltava fuori un pio magazzino di mattoni rossi, sormontato, a volte (ma soltanto negli esemplari più raffinati), da una campana racchiusa in una specie di gabbia per uccelli. Unica eccezione era la Chiesa Nuova: un edificio intonacato che, sopra alla porta principale, aveva un campanile quadrato con in cima quattro pinnacoli simili a robuste gambe di legno. In città tutte le insegne degli edifici pubblici erano negli stessi identici austeri caratteri bianchi e neri. La prigione avrebbe potuto essere l’ospedale, l’ospedale avrebbe potuto essere la prigione, il municipio avrebbe potuto essere o l’uno o l’altro oppure tutti e due, o anche qualsiasi altra cosa, perché nulla, nelle linee aggraziate di quegli edifici, serviva a identificarli. Fatti, fatti, fatti dappertutto nell’aspetto materiale della città; fatti, fatti, fatti dappertutto in quello immateriale. Era un fatto la scuola di M’Choakumchild, era un fatto la scuola di disegno, erano fatti i rapporti fra padrone e operaio; solo fatti si estendevano fra l’ospedale in cui si veniva alla luce e il cimitero, e quello che non si poteva esprimere in cifre, che non si poteva comperare al prezzo più basso e vendere a quello più alto, non esisteva, non sarebbe esistito mai, nei secoli dei secoli, amen. In una città così dedita al fatto, così trionfalmente sicura della sua supremazia, naturalmente tutto andava a gonfie vele, vero? Be’, non proprio. No? Povero me! No. Dai suoi altiforni la città non usciva splendente e radiosa come un pezzo d’oro purificato dal fuoco. C’era innanzitutto un mistero imbarazzante: chi erano i seguaci delle diciotto sette religiose? Di chiunque si trattasse non erano certamente gli operai. Strana sensazione quella che si provava alla domenica mattina, quando, passeggiando per le strade, ci si rendeva conto quanto fossero pochi coloro che, rispondendo al barbaro richiamo della campana che faceva impazzire la gente con i nervi a pezzi o ammalata, lasciavano i loro alloggi, le loro anguste stanze, gli angoli delle strade dove indugiavano con aria svogliata, guardando quelli che si recavano in chiesa o alla cappella, come se la cosa non li riguardasse affatto. Non erano soltanto i forestieri a notare tanta indifferenza; a Coketown stessa era sorta un’associazione i cui membri, a ogni sessione della camera dei Comuni, inoltravano indignate petizioni, sollecitando l’emanazione di una legge che imponesse con la forza a quella gente di diventare religiosa." da Tempi difficili, Garzanti, 1988 (Hard Times for These Times, 1854), cap V. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed